A version of our world where we are not dependent moment-by-moment on GPS tracking and Location Services is quickly becoming more and more unimaginable. So it was fascinating, then, that in his September 5th and 6th talks—delivered as part of Information Ecosystems: A Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar at the University of Pittsburgh—Matthew Edney asked that audience members think critically about these various mapping services and how deeply reliant we have become on them as a source of supposed “truth.” Long before GPS—and even long before TomTom, if you’re old enough to remember those—Edney pointed out that mapping and the so-called “field” of cartography has fundamentally shaped our conceptions of the world: how we visualize and are capable of visualizing it, how we are able to move and think about moving around it, and the many iterations of land-as-property documented over many centuries of maps. Edney’s new book, Cartography: The Ideal and Its History, does an excellent job of providing readers with a timeline of then-to-now.

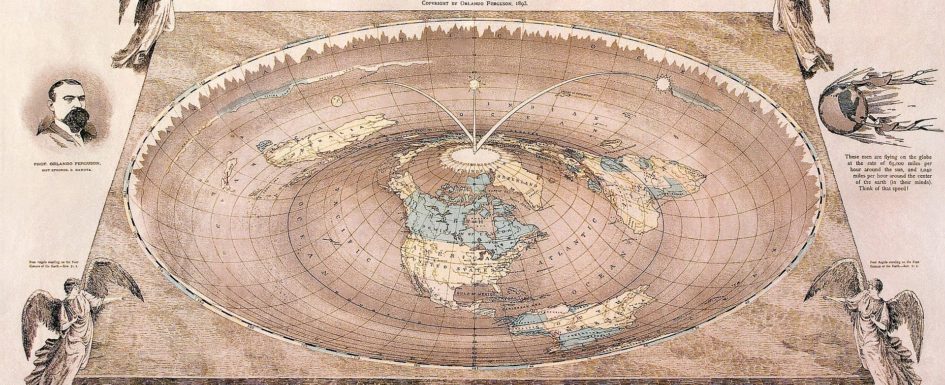

Cartography utilizes an impressively apt epilogue to the “Introduction”: “there is no such thing as cartography, and this is a book about it.” He helpfully framed his talks with this same quotation. By “there is no such thing as cartography,” he explained, he means that what cartography as a “field” purports to be is too loosely defined, too widely varying, too steeped in political motivation to cohere as a truly organized area of thought and practice; to quote Edney again, “the ideal of cartography is the entire belief system, while cartography is the fiction generated by the ideal.” Even by the 19th and 20th centuries, this ideal—that cartography is a set of methods that will result in “the map,” which we can trust as an unbiased and truthful representation of wherever that map mirrors—was so cemented in our transnational psyche that cartography was the topic of high-profile satires. These included Mark Twain’s “self-explanatory” map of Paris, and Lewis Carroll’s “Bellman’s Map,” otherwise colloquially known as a “Map of Nothing.” The late-19th century critiques on display here suggest that maps are only as useful as we have personal faith in them to be and, sometimes, this means that they are not very useful at all. Twain’s own commentary on the Parisian map pays special attention to the map maker’s temperamental influence; it was, as he puts it, the result of “sudden changes of mood in me, from deep melancholy to half insane tempests and cyclones of humor.”

Today, many of us—particularly the younger of us—have never driven anywhere, verified a bus route, found a restaurant, or asked for veterinary recommendations without the aid of the beautiful, easy-to-read little maps on our phones and tablets. These maps become ubiquitous, and therefore difficult to challenge—we take them for granted, often, as truthful, or correct, or at the very least a-political. After all, what kind of agenda could the turn-by-turn directions on my Apple Watch really be trying to push on me?

Edney effectively instilled in me some serious doubt about how and why I have become so completely reliant on these maps. These objects, whether digital or physical, he argues, are imbued with the same biases and flaws present in the humans who create them. Thus, no neutral methodology is applied and no truly nonfictional map is output. Edney challenges us, both in his new book and in these Seminar talks, to no longer conceive of maps as innocent or neutral objects but, rather, the product of a highly political and predominantly Western practice. And it doesn’t take a particularly long Internet search to find out that often—in fact, very often—this Western amalgamation of practices has gotten things pretty completely wrong; there are the early examples, like Ptolemy’s, or Martin Waldseemüller’s “World” maps, which might give everyone a good laugh. But even though we can all now conjure mental pictures of what the Earth actually looks like from outer space, maps and mapping practices are far from foolproof: there’s Mapquest’s many early-2000’s mapping errors in which drivers were sent down the wrong way of one-way streets, or Google’s problematic erasure of Brazil’s favelas.

These are, as Edney reminds us, the “genuine limitations” to the use of data and mapping. For one, he continued, it is incredibly difficult to actually keep track of and monitor the amount of map data that, for example, any state’s Department of Transportation is asked to keep up with in our hyper-located times. And we do not yet rely exclusively on an AI system capable of deciding what gets to appear on, for example, Google Maps or Apple, and what should not. Ultimately this is still a very human decision. Some real person out there is making undeniably biased decisions about which restaurants to foreground, which schools to highlight, and which streets to completely skip over within the Internet’s vast hierarchy of data.

Matthew Edney’s talks were affecting and informative in their challenges to link centuries-old cartographic practices to our contemporary reliance on GPS services. In both time periods, maps are politically manipulative; our minds cannot help but to equate the ratios and relationality of the map image to what is “out there”—and yet, there remains a distinct corporeal difference between the two. One Seminar participant recounted an anecdote in which someone was so fixated on the map of trees in front of him that he walked right into the tree actually in front of him, in the “out there.” Edney pointed out in response that yes, we must resist this urge to universalize and simplify our relationship to mapping the world; what is written in a map is there because someone had the power to make it so, not because it is the truth.

Stay tuned if you, like me, are thrilled to be taking part in such a rewarding series of talks this semester.