While all of the Sawyer Seminar speakers so far have been scholars or users of information ecosystems, Matt Lincoln is potentially unique in coding them. His Ph.D. in Art History, time as a data research specialist at the Getty Research Institute, and most recently, work as a research software engineer at Carnegie Mellon University have given him substantial knowledge about museums’ information systems, as well as the broader context of the seminar.

For Lincoln, “data” consists of collections of art and associated facts and metadata. In his public talk, entitled “Ways of Forgetting: The Librarian, The Historian, and the Machine,” Dr. Lincoln focused on a case study from his time at the Getty, in which he was working on a project restructuring the way art provenance data were organized in databases. Lincoln argued that depending on who the creator or end-user of the information would be (whether librarian, historian or computer), the way the data are structured can vary. A historian would likely prefer open-ended text fields in which to establish a rich context with details specific to the piece, whereas a librarian would opt to record the same details about every piece, and a computer would prefer the data to be stored in some highly structured format, with lists of predefined terms that can populate each field. On top of balancing these disparate goals, Lincoln cited a particularly poignant Jira ticket, which asked: “Are we doing transcription of existing documents or trying to represent reality?” This question might well be answered with “both” since the reality of provenance data is that it arises from collected documents and expert opinions.

At the Getty, the goal was to create linked open data — data that is organized and licensed such that it can be readily reused by others. Within the museum world, there is not a centralized database with information about all works of art — each museum maintains its own database, often in systems customized for that specific museum. Lincoln argued that this decentralization may have beneficial — many museums went above and beyond the kind of data that could have consistently be collected in the 1970s when interest in such a database first arose. Today, due to a lack of character limits and other constraints on databases, the systems in place can be more complete. However, linked open data would not necessitate the creation of a centralized database — it would simply specify a format and set of fields which could serve as a standard for museums cataloging works in the future. Specifying this format requires balancing the needs of archivists, historians, and of course, the ever-present computer.

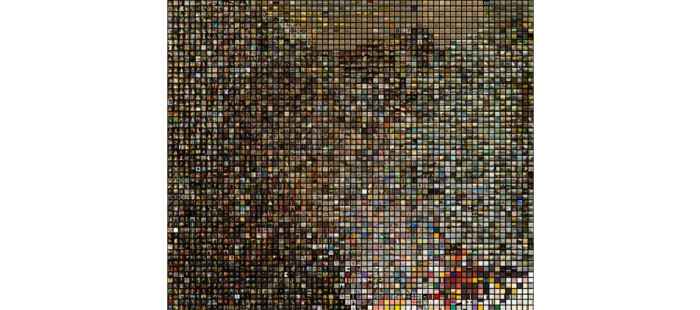

When considering presences and absences in the data, Lincoln noted that museums’ collections are somewhat like an iceberg — what’s on display is a tiny fraction of all the museum’s holdings. Further, a few items typically command the bulk of attention from curators. As linked open data about museum pieces becomes accessible and is used by developers, the public can learn about works that may not be displayed. For example, if a piece is visually similar to a more famous work, it may never be displayed in a gallery. However, thanks to a project Dr. Lincoln, seminar participant Sarah Reiff Conell, and their team built, one can swipe through visually similar artwork as perceived by a computer vision algorithm and neural net. Lincoln has also produced a project entitled Mechanical Kubler, which creates chronological paths through visually similar works, akin to calculating 6 degrees of separation between artwork.

Through efforts like these, the viewing public may discover art they would not otherwise encounter, enriching their museum experience. Lincoln also notes that efforts like these can indirectly benefit the museum a well, by increasing museum attendance. They get people interested in seeing more, rather than substituting for in-person visits.

Generating and using linked open data does present some challenges for the developer as well. When using structured data, with predefined terms to categorize works, some art falls outside these constraints. Examples include performance art, self-destructing pieces, and materials that degrade over time. More recently, born-digital works also offer some unique challenges in preservation — the evolution of technology may render file formats out of date, make hardware formats obsolete, or break links over time. To be successful, any format for open data that has a chance at viability must handle such exceptions.

A more morally weighty issue is categorizing art by non-Western artists using terms developed for American and European collections. This case reminded me of Safiya Noble’s analysis of the Library of Congress classification system, in which dated and in some cases, racist language was used to designate non-Western works as a deviation from the norm. The people who decide what art fits into which boxes, or more consequential still, what the boxes are, are in a position of power. Fortunately, the museums Lincoln spent time with took issues like these seriously. One example Lincoln cited was the British Museum working for years with Asian experts to develop an appropriate library of terms to describe Chinese art, translating terms for art from their language of origin rather than using inaccurate English substitutes.

In concluding, Dr. Lincoln offered advice on the subject of training and pedagogy to equip people to build and use linked open data and other systems. His unusual route to becoming a software engineer and the fact that he does not teach semester-long courses in his current role caused his advice to vary somewhat from that of most of the professors so far. To teach people in the humanities and social sciences to code, he suggested instructors adopt a model of situated learning. Students would work to create a deliverable, primarily learning to use tools to the extent necessary to make something work. Lincoln said that a process like this one can help people — even those with some background in programming — learn quickly what they don’t know, and fill in those gaps.

Lincoln’s blog is a testament to the power of open data and learning to code through the process of building projects — readers can see several efforts to bring museums and art to life. Through more accessible open data, it’s possible to enhance not just the experiences of librarians, historians, and computers accessing the data, but anyone with an interest in knowing more about art.