In his computational work, Colin Allen, distinguished professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, embraces the fact that the textual data he uses in his computational work often depends not on his choices, but on someone else’s. Data does not emerge, fully formed, for him and his colleagues to study. He discussed this characteristic of data when he addressed the Information Ecosystems Mellon Sawyer Seminar at the University of Pittsburgh on Friday, Feb. 28.

Data, as Joanna Drucker has memorably argued, isn’t data as much as it’s capta. If we remember the Latin meaning of data is “things given” while capta is “things taken,” Drucker’s argument makes sense. The stuff we generate in our experiments or gather in the world doesn’t exist naturally. Rather, it’s taken or made (in which case I suppose we’d call it facta). In Drucker’s formation, we are reminded that data isn’t neutral but often exists according to the individual choice of this or that researcher, or this or that curator.

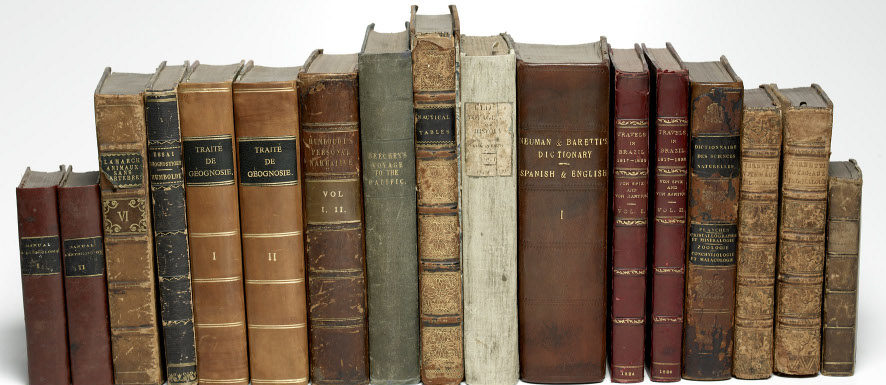

Allen points out that the textual corpus — that is, his data — he uses for one project, Darwin’s reading list, for example, yields its own data when he runs a topic model of the corpus. The topics produced by the model is data he can then interpret in his own work. In this way, Allen explained to me when I interviewed him for an upcoming episode of the Information Ecosystems podcast, data has a habit of begetting more data.

“I think it’s important to realize that take any information data from wherever it comes, do some transformations on it, [and]… that can become data for something else, whatever your pipeline is,” Allen explained when I interviewed him.

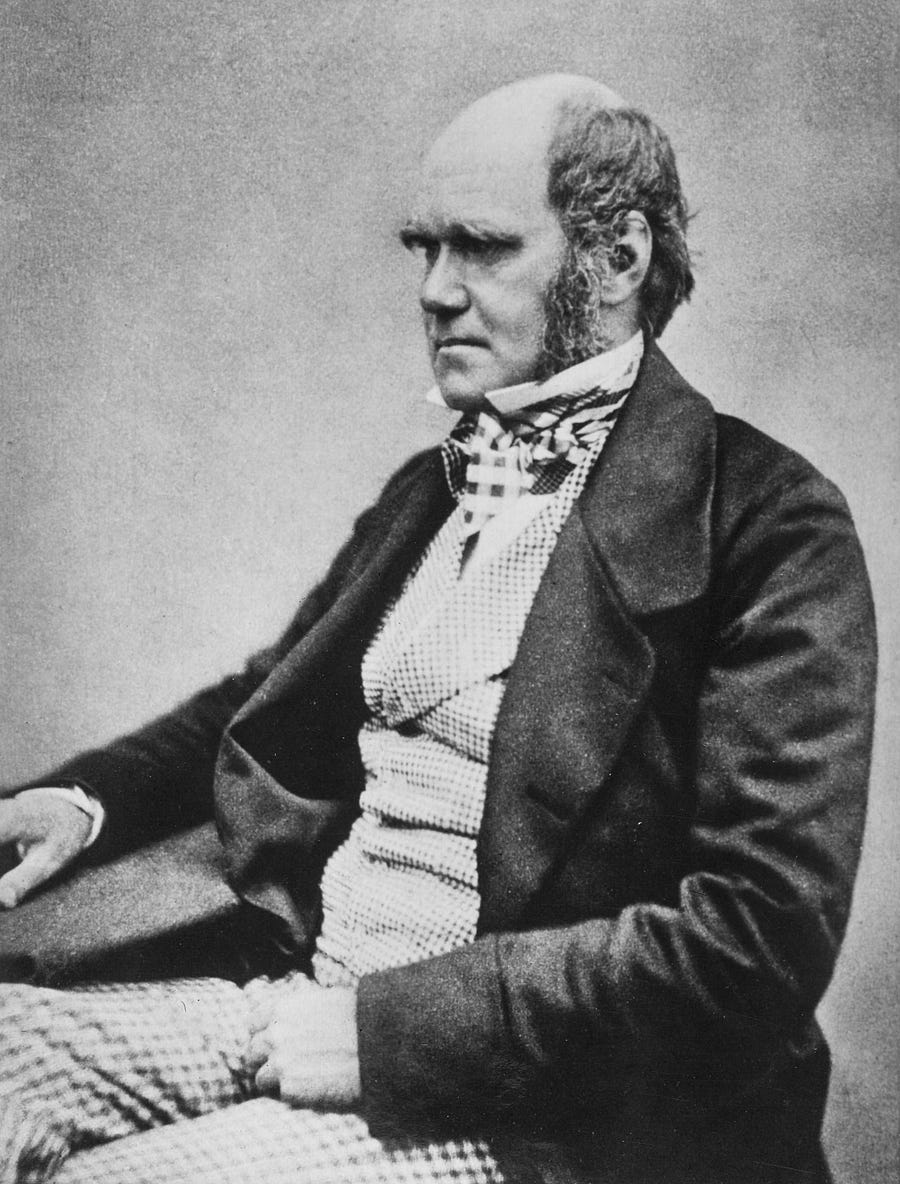

Take, for example, Allen’s 2017 article “Exploration and Exploitation of Victorian Science in Darwin’s Reading Notebooks,” coauthored with Jaimie Murdock and Simon DeDeo. In that article, Murdock, Allen, and DeDeo took as their initial dataset Charles Darwin’s reading history — which he faithfully recorded in a reading diary from 1837 to 1860 — and looked for changes in the famous scientist’s reading habits and how those changes may have influenced his writing. To look for those changes or influences, they used topic modeling, a popular computational method among humanists. Topic modeling works by assuming that any particular work contains inside it various topics, or themes, and, by running a statistical model, often latent Dirichlet allocation, multiple topics made up of lists of related words are produced and can be parsed by a researcher who is familiar with the text already. Allen shared some of his thoughts about how humanists approach topic modeling at his public lecture on Feb. 27.

In another article, this one coauthored with Andrew Ravenscroft and published in Digital Humanities Quarterly in 2019, Allen used topic modeling to try to locate the points in nineteenth century psychology texts where the authors most explicitly engage in their arguments. In both these articles, topic modeling is a tool used for exploration to help researchers locate certain information across a large corpus. The 2019 article is also interested in assisting students and scholars in “argument mapping to improve the identification, analysis and interpretation of the arguments.” In neither article is topic modeling of a curated dataset a means to an end, but rather produces data that can then be interpreted and used for other ends.

“We kind of go data, algorithm, output, [and] that becomes data for the next step. Then algorithm, output again,” he said in the interview.

When Allen discussed his work, particularly the article about Darwin’s reading habits, he acknowledges that he and his coauthors are not in control of curation of their initial dataset. Rather, they have to work with what Darwin chose to read, in the case of the 2017 article, or what is available in HathiTrust, in the case of the 2019 article. While HathiTrust has about 17 million digitized volumes from a consortium of university and research libraries, it is by no means exhaustive. As Allen pointed out to the Sawyer Seminar Friday, in the case of the psychology corpus, the collection online in 2020 is actually dependent on the purchasing choices of librarians more than a century ago.

Happily, perhaps, one of the texts Allen and Ravenscroft worked with in their 2019 article was The Animal Mind: A Text-Book of Comparative Psychology by Margaret Floy Washburn, the first woman to receive a PhD in psychology from the United States and the first woman to act as president of the American Psychological Association. That Allen and Ravenscroft wound up working with Washburn’s book was a case of what Allen, and several coauthors, referred to in the article as “guided serendipity” in a 2017 article in the Journal of Cultural Analytics. Thanks to their computational methods, her work comes once again to the fore, emerging from some 17 million texts in the HathiTrust collection.

Exploration and capturing of data computationally have that potential — to allow for serendipity, as with Darwin’s reading patterns, or for a reminder of an early pioneer of American psychology.

Briana Wipf is a second-year PhD student in the English department at the University of Pittsburgh, where she studies medieval literature and the digital humanities. She asked Dr. Allen, who also studies the philosophy of animal cognition, whether her dog likes her; Dr. Allen perhaps sagely demurred. Follow her on Twitter @briana_wipf.